LONDON — The decline of beauty. The compact but ambitious exhibition “Beauty in Decline” at the Colnaghi Gallery examines the concept of beauty and its inevitable decline through pan-historical, pan-geographical and pan-religious examples. The show ranges from ancient Rome and Egypt, Tibetan Buddhism and Christian-inspired vanitas to contemporary art. Such a wide range in commercial galleries could easily be interpreted as a calculated plan to sell disparate or rare works of art. However, it was independent curator Alfred Crenn who originally intended the museum concept. In finding a home in Colnaghi, Crenn assembled important pieces of privately owned work for this project. A particular example is the magnificent three-headed bust of Chamunda from 10th century India in Anish Kapoor’s collection.

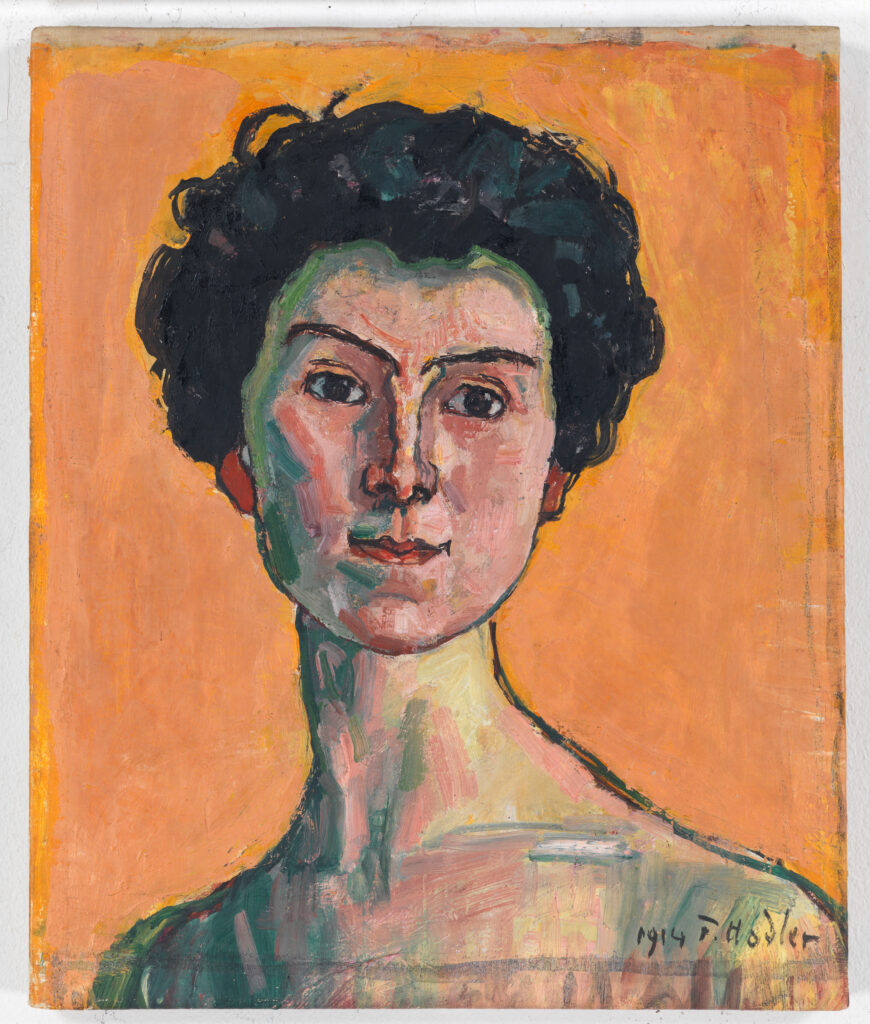

Attempting to identify intentional iconographic or stylistic similarities between works from such different times, places, and creeds is a futile exercise in spotting flukes. Rather, pleasure may be found in the contrasts and juxtapositions within a single landscape, complemented by Colnaghi’s intimate viewing space and the exhibition’s all-encompassing sensibilities: the brutality in temporality and even notions of decay. No. An interesting work is “Portrait of Clara Passe-Batier” (1914) by Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler. This is perhaps the only work in the exhibition whose sole purpose is to capture aesthetic beauty. It has a desolate atmosphere, surrounded by art that depicts themes of decay and death.

Installation view of “The Decline of Beauty.” The beauty of decline. At the Colnaghi Gallery in London. From left to right: “Image of a Priest” (possibly Priest of Min), Egypt, New Kingdom period (1391-1353 BC). Emil Burgush “Mummy of Princess Nestanebetisher of the 21st Dynasty”. “Sarcophagus Face”, Egypt (c. 942-715 BC)

One of the groups is the bronze painting “Death and the Miser” (undated) by Frans Franken the Younger. This warning piece depicts a looming skeleton in a loincloth playing the violin towards an old man who is surprised by his material wealth. Next to it are a stunning 19th-century Mongolian sitipatti, with two skeletons representing angry gods in the dance of eternal death, and a 16th-century kapala from Tibet, clearly real humans. There are ritual skulls made from the skulls of. Although each differs in purpose and execution and exemplifies different attitudes toward death in each culture, each still evokes similar anxieties and fears. Similarly, a Chinese (17th-early 18th-century) scholar’s stone is Swept Up (1999), a detailed pencil drawing of the remains of a floor swept into a random pile. are placed side by side. The common grayscale textures, jagged points, and irregularities formed by the chaos of nature reveal strange visual commonalities between the disparate works, emphasized by the curatorial arrangement.

The theme of beauty and its decline is most concentrated in Katherine Murphy’s gigantic, confrontational close-up painting Harry’s Nipples (2003), a classic example of the idealized body. It is concentrated in a small inner room that is paired with a statue of Asklepios in Rome. A small study of a female nude by Fantin Latour (undated) and a highly abstracted figure in enchanting pink, entitled “Blasser Nachtgeist” by Maria Lassnig (“Soul pallor”, circa 1990 to 1999). By bringing together such diverse and extreme treatments of body expression, the show demonstrates how historical attempts to identify and capture idealism in the human form have long been unstable and problematic. It suggests that.

It was perhaps fortunate that Kren’s idea landed in Colnaghi’s gallery space rather than in a facility. Because this quiet but deeply influential collection of works could lose its power as it grows in numbers. Such an ambitious scope works here precisely because of its focus. Conceptual gallery shows put sales aside and keep the concept refreshingly focused.

Sitipati – Dancing Skeletons, Mongolia (16th century), polychrome on bones, installation view of the private collection “Decline of Beauty”. The beauty of decline. At the Colnaghi Gallery in London. From left to right: Fantin-Latour “Etude de Femme”. “Statue of Aesculapius”, Roman period (ca. 100-150 AD). Katherine Murphy, Harry’s Nipples (2003), Kapala, Tibet (19th century), polychrome on bones, private collection. Head of Chamunda, northwest India, Rajasthan (early 11th century), sandstone Great Scholar Rock, Lake Taihu, China (17th-early 18th century), stone

Decline of beauty. The beauty of decline. On view at Colnaghi Gallery (26 Bury Street, London, UK) until November 8th. This exhibition was curated by Alfred Kren.