Illustration: Arnaud Boutin

Early one morning this past May, while the house was still asleep, I tiptoed into the kitchen and was assaulted by a strange smell.

I was, by then, inured to most new odors. A month before, our sons’ day care had closed unexpectedly, and, with nowhere else to go, seven children had taken over our two-bedroom rowhouse in Brooklyn, bringing all manner of aromas with them. But this one was different. It was sharper, less ambient than the usual cast of diaper trash and yogurt pouch and chewed-up stuffie. It did not hang in the air so much as cut through it. This was an outdoor smell.

I surveyed the kitchen. The counter was clean. The garbage can was closed. The window was cracked open. Then I saw our 20-pound rescue dog sulking under the table — and came inches from stepping, barefoot, in one of several streaks of shit that spackled the floor.

King Solomon had eaten the food the children had dropped, again. It had made him incontinent, again. And in three hours, the children would be back. They would be building train tracks and towers on the floor of our sandbox-size living room, dashing madly down creaky stairs to make it to the potty station we’d set up in the basement bathroom. They would be dancing to nursery rhymes that had already lodged themselves in my head on a loop — the lullaby about the light of the moon, the colonial march about crocodiles at war on the banks of the Nile. They would, once again, be feeding the dog, committing us to yet another morning spent furiously scrubbing the floors with Clorox before anyone arrived.

I looked at the dog and at the floor and asked myself when this ordeal would end.

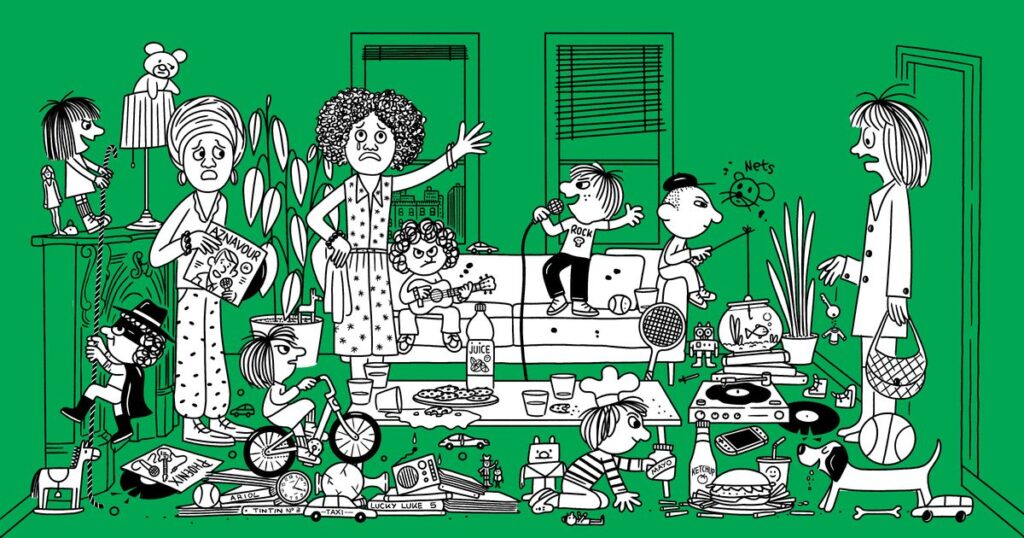

The author’s living room in her Brooklyn rowhouse.

Photo: Frankie Alduino

It all started with a push notification. On April 10, 2024, I got a message that all parents dread: I’d have to pick up my child from day care. Adi, my younger son, wasn’t sick or injured, but an inspector from the city was on-site and wouldn’t leave until all the children were gone.

That day happened to be Adi’s 2nd birthday, and I arrived to find him sobbing. It wasn’t just day care that was canceled — his party had been called off, and he was as sad and mad as you can be when you are turning 2 with no cake, no candles, no friends, and no songs. The two caregivers present looked shell-shocked; they were trying to calm upset children and panicking parents without fully understanding what was going on themselves. Through the crying and chaos, I heard the inspector, a woman contracted by the Office of Children and Family Services, say something about the day care’s license. There was a problem with it, but it wasn’t clear what it was or how long it would take to resolve. “I do hate to do this,” she told me as I gathered Adi’s belongings. “I can tell that the kids are so happy here.”

They were happy there. We were happy there. Our day care was French immersion, but it’s less fancy than it sounds. I grew up in the French part of Switzerland, and when my husband and I had just one child, we considered enrolling him in a bilingual program run by Swiss people in another part of Brooklyn. It had big gorgeous windows overlooking a lush backyard, and they made our 1-year-old son “interview” over Zoom. We balked when we realized that, even with its monthly $3,430 tuition, every staff member was not required to be vaccinated against COVID and lunch and storage for strollers were not provided.

Our day care was the scrappy, diasporic stepchild of French colonialism, employing caregivers from Togo, Guinea, Gabon, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burkina Faso, Algeria, and Morocco. It was a thousand dollars cheaper, and it didn’t charge by the minute if we were a little early or a missed-train late. It didn’t close on holidays of middling importance or for protracted summer breaks; the caregivers didn’t keep a ledger of borrowed diapers and socks or make pretentious statements about “academics.” They cooked healthy meals, gave the children sweet nicknames, and read to them. It was a bit more communal — strollers got stashed in a bathtub — and had a cozy informality hard to come by in New York.

The caregiver sent us home with Adi’s cake still in its box. We picked up his almost-4-year-old brother, Kian, at one of the day care’s sister locations, went home, and threw him the best birthday party we could. Adi blew out his candles and stuffed so much cake in his mouth that he puked. Then he played with his new garbage truck. From his perspective, all was forgotten.

I spent the evening texting with other parents to figure out how we would get through the following days. “If it’s a longer-term thing, we can accommodate a few kids if they send a teacher,” I wrote to the WhatsApp group. I’d just turned in the last draft of a book and had some time to help, and the caregivers were onboard. Other parents chimed in offering their apartments, too. The day care had been operating successfully for years; in my mind, “longer term” meant a week or two at most. This closure couldn’t go on for more than that, could it?

The next day, three people showed up at our doorstep: Remy and Chloe, two 3-year-old girls from Adi’s classroom, and a 28-year-old caregiver, Iris. As the children started their day with breakfast, potty, and “circle time,” I realized just how unprepared we were. We live in a narrow house with two bedrooms upstairs, a kitchen and living area on the ground floor, and a finished basement. We had babyproofed years ago, and the basement could be repurposed as a nap room, but there wasn’t much open space and the bathrooms were up or down a flight of stairs. The parents’ group chat, meanwhile, pinged steadily as we pieced together what had gone wrong.

The trouble, we learned, had started as a real-estate matter. Since 2021, the day care’s owner, Amia, had operated out of adjacent garden units in Park Slope. The brick buildings were run down, but they had cheap rent and — to the children’s delight — a big backyard. Last year, Amia learned that the buildings were going to be torn down at an unspecified date, likely to make room for high-end condos. Her landlord had filed permits for their demolition. At pickup and drop-off this past March, I started noticing contractors hanging around the building, hauling sacks of trash and debris from the vacant units upstairs. One day, construction workers showed up carrying odd-looking devices — air-quality monitors, they explained. I asked the people next door what they’d heard. The eviction was coming, they told me, but they were trying to negotiate for more time. Then asbestos-abatement notices began appearing on the walls.

The buildings’ owner, Harry Einhorn, fit every stereotype of the unscrupulous Brooklyn landlord; in 2013, he and his father, Victor, served eviction papers to a day care and a senior center on Christmas Eve. They’d warned Amia that they would turn off the heat to prepare for demolition (never mind the fact that doing so before a lease is over is considered an unlawful eviction in New York State). And true to their word, the day care’s heat abruptly shut off on a morning in mid-March, leaving the children shivering in their cots.

Parents, seeing the state of the buildings, had asked Amia if she had a plan. She did, she assured us, and, at the end of March 2024, she announced the day care would open two new locations in separate apartment buildings a few blocks away. On April 3, we brought the children in. The 24 kids were now split by age group between the buildings. Kian would be in one, Adi in the other.

There was a hitch. Before she was allowed to open the new sites, Amia had had to apply for brand-new day-care licenses. It was a byzantine process. For group family day cares like ours, which operate out of residential units, licenses are site and provider specific, so every classroom had to be registered separately and under a different person’s name. (Amia solved this by entering a partnership with her employees.) Although many of them had been certified for years, the caregivers had to submit new background-check documents, and each location had to pass a building inspection. Nose to tail, the process of getting a license can take up to 90 days if nothing goes wrong. And by move-in day, Amia’s licenses had yet to arrive.

Amia, a Cameroonian immigrant who started working in child care after moving to the States, opened her day care in 2021 using settlement money she’d received after being hit by a car. She knew that waiting three months before opening could put the day care out of business — she’d be covering payroll, utilities, and rents without earning a dime. Faced with an unlawful eviction, parents and staff who depended on her, and piles of new bills, she took a gamble. She figured she would move the kids into the new spaces and hope that the updated licenses and background checks would come through before officials caught wind. But on April 10, the inspector, a local health-department employee sent by OCFS, came knocking. The children would have to go home until the day care’s approvals had made their way through the state’s licensing system.

In the weeks that followed, ad hoc nursery schools formed across Brooklyn to accommodate the two dozen displaced children. We were the micro-generation of parents that narrowly skirted the miseries of COVID-related closures, but now we found ourselves in “pods.” They were organized geographically so parents wouldn’t have to travel far for drop-offs; some would later disband or move when neighbors complained or families had had enough. Meanwhile, ours grew from four to five, five to six, then, at its peak, seven children under the age of 4 playing, eating, sleeping, and screaming in the kitchen, the living room, and the basement.

The children came and went depending on whether they got sick or had grandparents in town, but we did end up with regulars. There was Kian’s best friend, Timmy, an almost-4-year-old with a sweet face and the appetite of a grown man. The two 3-year-old girls stuck around too. They started calling me Maman, which everyone found hilarious except Adi. “Ma maman,” he’d object, clinging to my leg like a sloth. And there was Ben, who had just become a big brother. He arrived after his parents tried to host a smaller group but threw in the towel after a week — it was just too much with a new baby. The caregivers were shuffled around as pods assembled and dissolved. In some homes, as many as four or five children could wind up with one caregiver, but we were lucky to have two: Iris and Raissa.

What even happens at day care, anyway? Before the closure, we’d receive curated videos and photos of painting sessions, dance parties, and free play through an app called Brightwheel. But the actual rhythm of a day at day care was of another world. Day care exists for this purpose: to distance working parents from the tears and tantrums and blowouts that mark every passing hour in the company of toddlers. I felt awkward watching Iris and Raissa take care of my children in my house while I sat around, and I could tell they felt weird being watched as well. They brought lunch and took turns eating outside. They apologized for everything, which made me feel even more useless. My husband, who works from home two days a week, took to hiding in our bedroom, emerging only to make a sandwich that he’d eat on the bedroom floor.

Soon, our motley crew slouched into a routine. The children would get dropped off at nine. They would have a snack, play with toys, sit in a circle singing, and read books. At 11, they’d crowd around our table for lunch, after which they’d nap — my sons in their beds upstairs, the remaining five in the basement.

If this all sounds civilized enough, it was, in practice, a circus: constant noise, the kinetic energy of seven small, restless bodies. Cracker dust formed a layer of sediment between couch cushions. The cabinets and doorknobs were always sticky. There were yogurt smears on the wall, crayons and toys on every surface. The basement had once been my office; now, it was colonized by a sea of portable cribs, blankets and stuffies, as well as diaper pads, rash cream, and packet upon packet of baby wipes. Initially, I put the cribs away at the end of the day. Then I stopped bothering.

From what would have been Kian’s new classroom in Park Slope, Amia found herself operating a de facto catering service. Her day care provides meals, which, in normal times, she would cook in the morning while her colleagues minded the children. Now that the children were spread across half a dozen homes, she had to adjust. She would wake before dawn and cook breakfast, hot lunch, and snacks and portion them into Tupperware containers, then label them for the caregivers to pick up. Then she’d shop for supplies and start food prep for the next day while fielding calls and messages from aggrieved parents. “I didn’t sleep. Every morning, I got up and asked myself, Will I get the license today? ” she said. She started losing her hair and having chest pain.

Because the pods had been organized geographically, the children often ended up being different ages; Rose, one of the caregivers, was charged with a group that included a 4-year-old, two toddlers, and a baby, none of whom ate the same food or stuck to the same schedule. “The bigger kids were awake when the baby slept. The baby was awake when they slept. I never got a break,” she said. (I’ve changed her name, as well as those of her colleagues, so as not to threaten their immigration statuses. The children’s names, except for mine, have been changed too.)

The hardest part, all the caregivers told me later, was the isolation. Before the closure, a caregiver always had at least two or three colleagues around to watch the kids if she needed to use the bathroom or take a break; now, she was in an unfamiliar setting, alone or with one other person, juggling activity-organizing, meal preparation, diaper-changing, and potty breaks while keeping an eye on the children. “At the day care, if there was a problem, you could talk about it with other people,” Rose said. “Alone with four kids, I was so scared there would be an accident and I would have to tell parents something happened to their child.” It’s not as though our home had a license, either — our tables had sharp edges; our floor was slippery. There was no emergency exit or a backyard for the children to get fresh air, save for a desolate patch of bricks.

April became May, yet we remained in license limbo. In order to get licensed, each of Amia’s new sites had to pass a building inspection. The initial visits had taken place already, but Location One, where Adi had been, was still awaiting a second inspection to approve an emergency exit. The Office of Children and Family Services also had to review the paperwork, which included the background checks. Location Two, where Kian had been with the older children, had passed its building inspection and submitted the requisite documents; all that was left, to the best of our knowledge, was for the state to finish processing them. One evening, after weeks of fielding calls from parents, Amia convened us at one of the shuttered day cares, and what began as a meeting about bureaucracy ended in tearful pledges of solidarity. We’d hung on for this long and weren’t ready to give up yet. Many of the children had been with Amia and her staff since they were tiny babies.

Still standing was a third classroom a few blocks away, which Amia had opened in early 2024 for babies 6 weeks to 2 years old. Her licensor had told her the paperwork would take around 30 days to clear, but after two months and no license, she began admitting children from her growing wait list because she could not afford the rent otherwise. By May, Amia was at full capacity — but still had no word from OCFS.

On May 7, the parents’ WhatsApp group exploded. The third location had been busted by an inspector who had responded to an anonymous 311 call claiming the space was unsafe. The day care would have to vacate immediately and remain closed until an inspector made three surprise visits to ensure it was complying with the suspension and the license was granted. When one parent went to pick up her daughter, she pressed the inspector: Everything had been fine for months. What happened?

A parent had called, the inspector revealed. They had reported that the number of kids on-site exceeded the state’s caregiver-child ratios (Amia later said the ratio was the result of having to find spots for kids affected by the other shutdowns). In back channels, parents quickly formed their suspicions about the identity of the caller: a mother who posted, and immediately deleted, a number of messages to the group chat prefaced with “It definitely wasn’t me, but” and went on to justify a hypothetical 311 call. This family left the day care for good during the closure.

Now, a dozen more families were in the same situation as us: displaced and in disarray, improvising nanny shares in small apartments. But for them, there was a twist: State rules stipulate that two children can remain in a day care with a caregiver while they await their licenses, and the parents argued bitterly about how to share the spots. (This had been true for the other two spaces as well. Kian’s former classroom did host two children, but it didn’t occur to us to fight about it; Adi’s didn’t, for lack of staff.) One day, at the playground, a friend with a 1-year-old in this group confronted another mother: Could they at least discuss rotating kids through the space? As my friend recalls, the mother — who had secured a coveted spot by simply asking for it first — told her she felt villainized by the suggestion. Days later, my friend saw her cross the street to avoid her. “I naïvely thought we were all in it together,” said my friend. “But it turned out some of the parents just wanted to make sure their lives weren’t disrupted.” The drama, she said, left her “outraged and obsessed.”

I, too, became obsessed. The 311 incident filled me with rage and indignation. How could she? And the bureaucratic cesspool of it all had morphed me into something I had always hoped to avoid becoming: a pushy, entitled Brooklyn parent. Which is how I found myself, on May 8, sitting on a pleather sofa next to a fake Christmas tree in the lobby of the Office of Children and Family Services. Amia, another parent named Lauren, and I were there to speak to one of our licensors to figure out what was causing the delays.

When the inspector met us in the lobby, she revealed that she had not processed the forms Amia submitted in early March. That, apparently, was the day care’s fault. The employee claimed our paperwork was missing crucial information: Two unmarried caregivers had not filled out a box asking for their maiden name (“You should have put N/A,” she said), and Amia had skipped a section that required her to describe one location’s backyard.

“But there’s nothing in the backyard,” Amia protested. “It’s empty.”

“You have to put something,” she said. “Just draw a square with a swing.”

We filled out the papers in front of her to her apparent satisfaction. “I’ll send it off today,” she promised. “It’ll be another one to two weeks.”

Two days later, she emailed Amia. She had still not sent off the background checks and the form with the fictitious swing; she could not understand a word on one of the papers. The word was Cameroon: Amia’s place of birth.

When I heard the news from Amia on a Friday afternoon, I called the inspector’s desk. Why hadn’t she asked us about it there, in the office lobby? We’d lost three precious business days for no reason.

“I understand your situation,” she replied. “I have a daughter in day care too.”

It occurred to me that this was the nature of bureaucracy: the separation of people from their paperwork. She had a line to toe for the system to work and for the state to show it was taking care of children. We just happened to be on the other side.

At the playground on weekends, I began telling parents what was going on. It turned out we were not alone: It seemed as though every third family had needed, at one point, to scrape together temporary child-care arrangements because of a lost or suspended day-care license. It wasn’t always possible to find another day care (according to the think tank the 5Boro Institute, there’s only one licensed day-care slot in New York City for every two children under the age of 5), so some resorted to getting babysitters or hiring the caregivers independently or forming pods like ours. As parents, we understood why the licensing process exists: The rules around emergency exits, student-teacher ratios, and background checks are there to keep our children safe, and no amount of uninterrupted day care is more important than that. In a statement, OCFS said a version of this too. “Licensing or registration of child care providers in New York State involves multiple activities, which promote the health and safety of children in care, and cannot be compromised,” a representative said. We knew the day care had violated the rules, and Amia admitted it, too. Still, it felt as though the system’s design had an unintended effect of making it as hard as possible for an ordinary person to run precisely the kind of small business on which the entire city depends.

For the past five years, the national conversation around child care has revolved around its cost. But child care is not just preposterously expensive; it’s also a difficult and unforgiving business to run, especially for those doing it by the book. Larger child-care centers and private-equity-backed chains might be able to afford to hire professionals to handle compliance, but for small operations — which are often run by immigrant women — the time and money aren’t there to wrangle building inspectors and licensors, fill out paperwork (which is not always in the owners’ first language), and launch the pressure campaign to get it all done quickly.

I kept asking myself, How is anyone who spends their day caring for small children supposed to navigate all this? In this case, Amia had us. We were doctors, lawyers, engineers, teachers, and investigative journalists with the time and energy to pore over checklists and worksheets and rules and regulations. Even so, we could barely make sense of what was required to obtain a license, who to call for guidance, and why it was taking so long.

The result is that many of the city’s smaller day cares are one eviction, illness, unexpected expense, or bureaucratic error away from shuttering. In the city in particular, the high cost of housing makes it even harder to weather something like an eviction or a rent hike. “We hear from providers all the time who are in the midst of a crisis,” said Lauren Melodia, who researches home-based day care at the New School’s Center for New York City Affairs. For these small-business owners, Melodia said, there isn’t a centralized desk or point person they can call for advice or assistance. And while local and state politicians have campaigned on making child care more affordable through subsidies and expanded school programs, those proposals don’t make these businesses easier to open and operate — and fixing licensing procedures hardly makes for a sexy slogan.

By mid-May, we were losing it. One child (for all I know, one of mine) took to systematically unplugging every electrical appliance within reach every single day. Another child (again, possibly mine) drew all over the couch in black marker. The caregivers told me that the dog had begun participating in the daily dance sessions. It sounded cute — a dog dancing with babies! — until I realized he was probably confused and trying to hump a kid’s leg. I’d wake at night panicking about everything that could go wrong, from children falling down stairs to King biting someone. Or I worried our efforts would lead nowhere and the day care would shut down after all. The stakes felt higher than ever: Amid the chaos, the children had grown even more attached to Iris and Raissa, as had I. My husband had more practical things on his mind, like liability: Should we have the parents sign a waiver? We found a form online but gave up because the printer stopped working.

The parents continued to pay tuition; we wanted Amia to stay in business and for our children’s beloved caregivers to keep their jobs. But when I learned that a friend’s cousin used to live upstairs from the original day care, I got the landlord’s number and requested $1,234 on Venmo with a note: “This is what a week of day care costs for the two children that you evicted by turning off the heat.” (It was ignored, and the Einhorns did not respond for comment.)

Sensing my presence at home was more disruptive than helpful, I started making myself scarce, working from cafés or a friend’s place. In exile, I took up an unpaid, part-time job as the day care’s expediter and scheduled the follow-up building inspections with Amia. Joining us was Tony, another day-care parent who, like me, was deep in the bureaucratic morass — so deep that he found himself boring his friends to death with stories of our stultifying administrative exploits. “You know you’re thinking too much about something when you start copying and resending text from one text chain to another one,” he said. “It’s 300 words, but they need to hear about it too: ‘Look at what’s happening with my day care.’”

The day was sweltering, but Tony showed up for the inspection in a suit and tie (“If they think I work at Goldman Sachs, they might take me more seriously,” he said), and I spent a day grilling the inspector to make sure we hadn’t missed a step that would slow us down. In both locations, he wanted us to rearrange the furniture in the neighbor’s backyard to clear the path for an emergency exit. The neighbors had agreed, but one of them wasn’t home, so I did what I could. I trespassed.

Meanwhile, the children were growing feral: tearing around the house, throwing tantrums, fighting over toys, and passing around untold viruses, which led us to close shop for a few days. Kian, the eldest of the bunch, took on a dictatorial air and started bossing his classmates around. I heard my own words repeated in a toddler’s imperious tone: “No eating on the couch! Pee goes in the potty!”

Afternoons were for outings, but more often than not, the kids would be stuck inside. Only a few of them could be counted on to walk in a straight line independently, and, as Iris and Raissa pointed out to me, it was physiologically impossible for two adults to hold three hands while pushing four strollers at the same time. “Hi everyone, I am writing to ask you all for help,” I wrote to the parents’ WhatsApp group in May. “We have rain on the forecast all week, and my kids and I are going to lose the last bit of sanity we have left if they don’t leave the house (remember, Kian and Adi are home *all the time*). Can each of you plan and/or chaperone an activity for each day?”

With help, our pod took trips to the children’s museum, the botanic garden, the neighbor’s yard to feed the chickens. Some parents apologized for not being able to make it: They worked full time in offices. Others barely responded. “Some people just weren’t very helpful,” said one mother who escorted the kids with her newborn to get ice cream more times than I can count. “I thought it was them being French? Some would pick the kids up and just complain about things. That’s what French people do.” (This mother is French.) Out of desperation, I bought a large wagon that fit four children, which helped Iris and Raissa take them to the playground.

A mile away, in a Clinton Hill duplex, a pod from our day care that had formed around the same time as ours — comprising a baby, three toddlers, and one caregiver — was struggling to find its footing. Yoko, one of the host parents, worked from home, and “if my son saw me duck into a room, he’d go to the door and lie on his back and kick and scream,” she said. Also in the pod was Harry, the 4-year-old son of Lauren, the mother who had accompanied us to OCFS. Lauren had just had a baby, and it seemed as though Harry was finding the changes (a brand-new sibling, the shuffling between houses) destabilizing. “Harry regressed a bit,” Lauren observed. “He was talking like a baby.”

One day, the pod’s caregiver was stretched so thin that she left the baby on the changing table and he rolled off. The baby was fine, but the incident rattled everyone, and Amia asked her to leave. “It shouldn’t have happened, but these women are not nannies,” Lauren said. “It was a lot to handle this many kids with no help and infrastructure.” The caregiver was replaced by Rose and then by another teacher named Mila. Mila was unsurprised by the administrative purgatory, she told me: It reminded her of how things worked in her home country of Burkina Faso.

By then, the parents had stopped with the niceties at drop-off and pickup. No more chitchat about our children, no more commiserating about the license. They showed up, took their kids, and left. It bothered me at first — we were day-care parents, not a day care! — until I looked around. What was this if not a day care? The worst part was not knowing when it would end. Every morning we hoped for good news, and every day concluded with none. At the real day-care site, furniture-rearranging for the building inspector did not bring about a speedy resolution. He’d told us that everything looked good to him, but it was now up to his supervisor to sign off, and Amia had still not heard back. The OCFS representatives and the state senators’ offices we’d contacted kept insisting things were moving at an appropriate pace.

In the second half of May, I went out of town for work and followed from afar as the other parents went back to the OCFS office to agitate more. Their interactions, over the phone and in person, were growing increasingly tense. One father may or may not have called an administrator stupid to his face. After a demoralizing email claimed Amia’s entire background check was missing, the parents and Amia made an emergency office visit. There, they learned that the office had inserted errors into the paperwork, inverting her first and last names and thus losing track of her file. This had prevented Location Two, Kian’s classroom, from opening, possibly for months.

The parents intervened — the supervisor said that “apparently, it’s a common mistake,” one father reported — and got things moving. But it is not unreasonable to wonder what would have happened had a group of us not cultivated a forensic obsession with the processes.

On May 21, the license for Adi’s classroom was approved. The younger children in our pod went back the next day, and we were down to a more manageable three: Kian, Timmy, and a straggler displaced from a just-disbanded pod. The house started smelling better right away; these kids were out of diapers. Then, on May 28, Amia learned the suspension prompted by the 311 parent had been lifted. The three requisite inspections had taken place in surprisingly quick succession. She also received notice that the remaining paperwork for that third location had been approved, too. The license was granted, and the littlest children could return. The group chat exploded into triumphant, tearful emoji. Only one classroom, Kian’s, remained in limbo.

Our efforts had begun to pay off, but at the Clinton Hill pod, the situation was reaching a breaking point. The host family had grown exhausted, so the pod had relocated to Lauren’s two-bedroom apartment down the street. Iris, restationed there from our house, found herself caring for a baby — the same one who had fallen from the table — as well as his 3-year-old sister, a 3½-year-old named Ray, and 4-year-old Harry. “There was no Pack ’n Play, no crib, and Iris was trying to get the baby to sleep on a mattress on the ground,” said Lauren. She was helping Iris as best she could while caring for her new baby, who also needed to go down for a nap. All the while, the bigger kids were shouting, throwing toys, and keeping the babies awake. “I tried so hard to keep it together, but the stress accumulated,” Iris said. “I was cleaning up, the baby was crying, then Ray pooped on the floor. And I started crying. I couldn’t take it.”

While this scene was unfolding at Lauren’s, I was waiting for the train to meet Amia and Tony. It was May 31, and we were heading to the OCFS office to agitate — as it happens, for what would be the last time. (“I think God saw me and heard me,” Iris later told me. “God felt it.”) The license for Kian’s classroom should have been ready by then. The online portal told us the background checks were complete, the other paperwork was in, and the building inspection had been cleared for over a month. We were but a few mouse clicks from a full reopening.

The plastic Christmas tree was still in its dusty corner. But the person we’d come to speak to was not there.

“What do you mean?” I asked the receptionist. “We have an appointment.”

“Things happen,” she said.

“Is there anyone else we can talk to?”

“No,” she said. Everyone was out.

“So what are we supposed to do?”

“Email him.”

We had emailed; we’d gotten nowhere. That was why we were here. She told us to call, but we had only his desk number.

I saw the world go black. I don’t remember what I said — probably something about seven children, two months, can’t work, no end in sight.

The receptionist began to scold me: I would get nowhere by being this aggressive, she was saying, and I could not take it out on her. She got up from her desk and walked toward me. I was pretty sure we’d be escorted out. Now she was staring into my eyes. “Are you okay?” she asked.

I blinked.

“Are you okay?”

What?

“No,” I said. “I’m not okay. I haven’t been okay for two months, and I won’t be okay until my kids are back in the day care we are paying for and can’t use because of this -nonsense we’re dealing with.”

Another pause.

“Do you need a hug?”

I let myself be hugged.

“Now go wait in this conference room. I’ll go get them.”

We sat, stunned. So there was someone there. They had been there all along. Moments later, a supervisor we’d never seen before came into the room. She reviewed our case and said everything was fine. She was going to print the license now.

We sat a little longer. Then the supervisor came back. She was trying to print the license but was getting a technical error. We could not reopen the day care without this piece of paper. She would go back and try again. The second time, the printer worked.

The following Monday, I hauled my children down the stairs of our subway station, rode four stops, and dropped them off in their respective classrooms, which were now fully licensed. We’d crossed the T’s and dotted the I’s and done everything the bureaucrats had asked for. Inside, nothing — not one thing — had changed.

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the October 7, 2024, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the October 7, 2024, issue of

New York Magazine.

See All