Percentage of reported barriers to AUD treatment by parenting status. Credit: PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0301810

A woman came in crying. She was disheveled, pregnant, and appeared to be drunk. She had a 5-year-old girl who sought help at the crisis center where Anna Shchetinina volunteered.

The mother got the help she needed. She sobered up, left her abusive partner, and eventually found a job in the medical field. Even after 15 years, Shchetinina still can’t stop thinking about her children.

“At the time, I didn’t realize that a mother’s drinking would probably affect the lives of her children as a whole, but now I understand that every decision counts, especially during sensitive and critical times. ” she said.

“Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder is a very special condition. Although 100% preventable, there is no cure and it has very serious cognitive, behavioral and physical effects.”

In April, Shchetinina published a study in PLOS ONE examining the prevalence of alcohol use disorders in pregnant and parenting women.

This research formed the basis of her doctoral research at Harvard’s TH Chan School of Public Health, where she studies the lifelong risks associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Among the potential effects are fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, the most severe form of which is fetal alcohol syndrome.

In the worst case scenario, the mother loses the pregnancy. Even if the baby survives, the effects often go unnoticed until school age, when children typically develop independent activities, behaviors, and even daily routines (waking up in the morning, making the bed, getting dressed, etc.). (wearing) becomes difficult. The damage caused by prenatal alcohol exposure can affect memory, self-control, emotions, attention, and problem-solving over time.

“The disease is usually diagnosed when the child starts school, but by then it can be difficult to manage,” Shchetinina says. “Diagnosis is not easy after so much time has passed. We may not have a clear record of the pregnancy. If it’s been six years, the mother may have no idea what she did during those nine months. You may not remember everything.”

“Also, some of the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure are similar to the effects of other adverse experiences, such as abuse and neglect. Diagnosis becomes increasingly difficult as time passes.”

Shchetinina said the first widely read scientific paper on the risks of drinking alcohol during pregnancy was published in 1973. Research on lasting effects remains lacking. In her research at Harvard University, she used data from three large studies (two in the United States and one in Europe) to uncover long-term effects.

“There are so many unknowns in this field,” she says. “We are just beginning to understand how drinking affects adult health. What happens to people who are exposed to alcohol prenatally as adults?”

She might have never asked that question had it not been for the mother she met 15 years ago at a crisis center in her hometown of Petrozavodsk, a Russian city about 420 miles from St. Petersburg. I don’t know. St. Petersburg.

“It was just heartbreaking,” said Shchetinina, a law student and volunteer at the center at the time. “I started learning more and more about the subject and became more and more interested.”

The crisis center was affiliated with a Minnesota nonprofit focused on fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, now called Proof Alliance. Representatives of the organization visited Petrozavodsk to discuss the dangers of drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Shchetinina listened, learned, and ultimately decided to quit her law practice and focus on public health head-on.

She came to the United States under the Fulbright Program, an educational exchange program sponsored by the U.S. government, and earned a master’s degree in public health from the University of Minnesota. Her next stop was Chan School.

Shchetinina plans to graduate in 2026 and continue her studies, most likely in the United States because of the dramatic changes in Russia since she left. The crisis center was closed after the invasion of Ukraine, and Shchetynina’s opposition to the conflict could put her at risk, she said.

In an April paper, Shchetinina and her doctoral advisor Natalie Slopen, assistant professor of social and behavioral sciences, used data from the 2015-2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health to estimate the reproductive age of the United States. We investigated alcohol use among women. They looked at responses from 120,000 women aged 18 to 49. 3% are pregnant, half are raising at least one child but not pregnant, and the remainder are neither pregnant nor raising a child.

Results showed that approximately 13% of non-pregnant and childless women had drinking habits that met the definition of an alcohol use disorder, but only 4% were receiving treatment. It was done. The disease was about half as common in the pregnant and parenting group, ranging from 6.3% to 6.6%, but only 5% of women received treatment, and large treatment disparities remain. I was there.

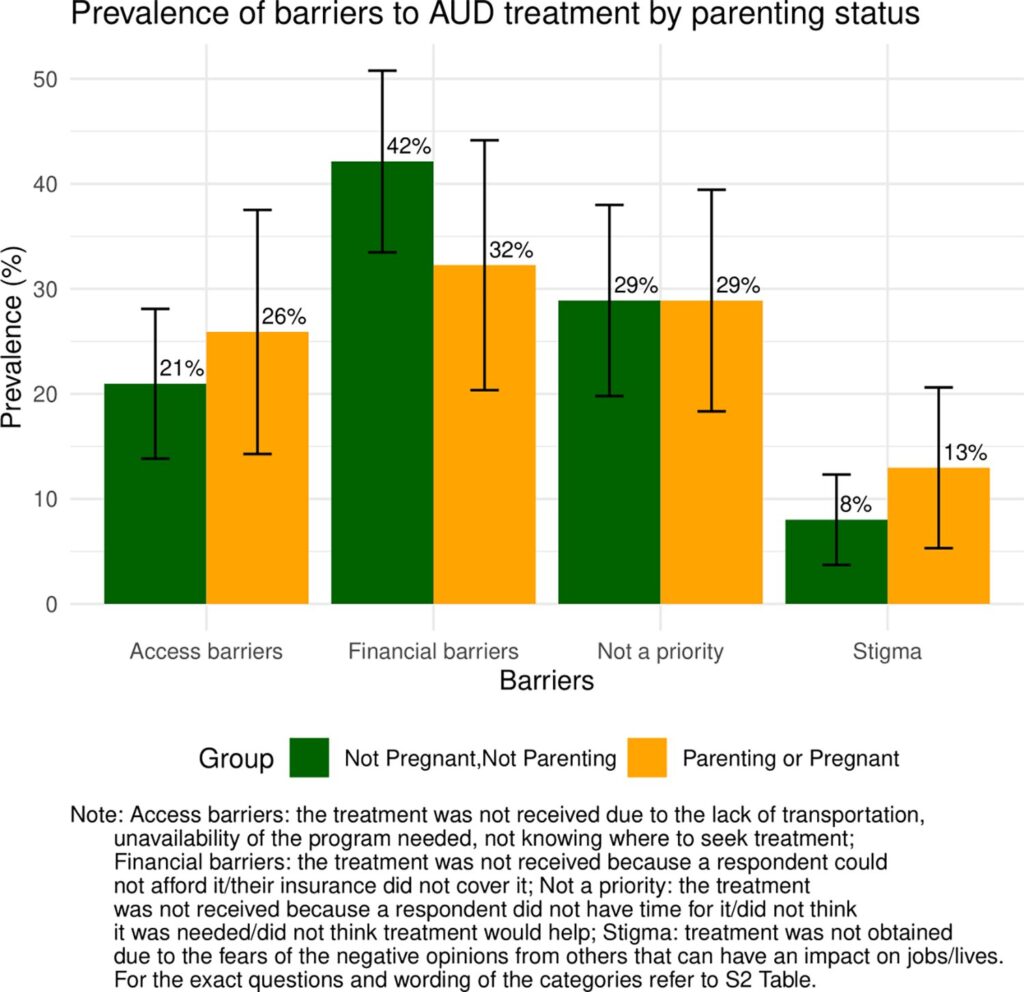

Slopen said the study provided experts with up-to-date information on the year of the pandemic, and that surveys showed an increase in drinking among women. We also looked at barriers to treatment and took steps to increase access.

The cost of treatment is higher for people with insurance such as Medicaid or private insurance, and respondents said financial barriers were a barrier to receiving treatment. For some, treatment was not a priority, but Shchetinina believes this may be due to the stigma against women, especially pregnant women, who consume alcohol.

“It is important to characterize the treatment needs and barriers that exist for individuals who experience alcohol use disorder and require treatment. “It’s important for both,” Slopen said. People who may become pregnant in the future. ”

Shchetinina agreed, adding that the findings also highlight the need for better interventions for non-pregnant and non-parenting women, who have high rates of alcohol use disorders. She noted that the results showed that women who were arrested or had a history of arrest received treatment more frequently. This may indicate that the greatest barrier to entry to care exists.

“We found that women with a history of arrest were more likely to receive treatment, meaning that being arrested may have been an entry point into the treatment system,” she says. “But the justice system that serves as the gateway to health care is flawed and should not be the easiest path to getting help. Health care providers are becoming more proactive and society is becoming more cooperative. It needs to be.”

Further information: Anna Shchetinina et al, Unmet need for alcohol use disorder treatment in reproductive-age women with an emphasis on the U.S. pregnant and parenting population: Findings from the NSDUH 2015–2021, PLOS ONE (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0301810

Provided by Harvard University

This article was published courtesy of the Harvard Gazette, the official newspaper of Harvard University. For more university news, visit Harvard.edu.

Citation: Shedding light on alcohol’s long shadow in pregnant and parenting women (October 4, 2024) https://medicalxpress.com/news/2024-10-alcohol-shadow-pregnant-parenting-women. Retrieved October 5, 2024 from html

This document is subject to copyright. No part may be reproduced without written permission, except in fair dealing for personal study or research purposes. Content is provided for informational purposes only.