Date and time: Tuesday, July 30, 2024

Contact: Interior_Press@ios.doi.gov

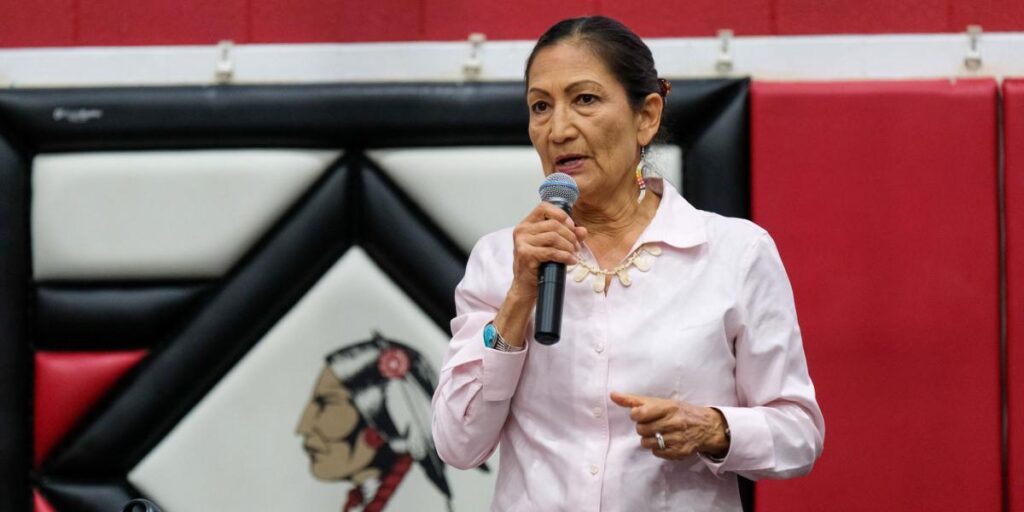

WASHINGTON — The Department of the Interior today announced that the federal Indian residential school system launched in June 2021 by Secretary Deb Haaland is the first-ever comprehensive effort by the federal government to recognize problems with past federal Indian residential school policies. The next steps for the initiative were announced. It aims to address intergenerational impacts in Indigenous communities and highlight past and present trauma.

The Department has released the second and final volume of the research report requested as part of this initiative, led by Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Brian Newland. Volume 2 builds on the first edition published in May 2022 and includes information on deaths of mourners, number of burial sites, participation of religious institutions and organizations, and federal funds spent to operate these sites. We have significantly expanded the number and details of our facilities. It also includes policy recommendations for Congress and the executive branch to consider as we continue to chart a path to healing and relief for Indigenous communities.

“The federal government, facilitated by the First Department’s initiative and through the federal Indian Residential School Policy, separates children from their families, denies their identities, and steals from them their Native foundational language, culture, and connections. These policies have caused lasting trauma in Indigenous communities, which the Biden-Harris Administration is working tirelessly to repair,” Secretary Haaland said. “I am extremely proud of the hundreds of Home Office employees, many of whom are Indigenous, who took the time and effort to thoroughly complete this investigation to provide an accurate and honest picture. The road to healing does not end with this report; it is just the beginning.”

“For the first time in U.S. history, the federal government has revealed its role in operating historic Indian residential schools that forcibly confined and assimilated Native American children. further proof of what we have known for generations: that federal policies were designed to defeat us, seize our territory, and destroy our culture and way of life. “There are,” said Assistant Secretary Newland. “There is no denying that these policies have failed, and we must now devote every resource to strengthening what they failed to destroy. We must ensure that this effort is sustained and that the federal government, It is important that state and tribal governments build on the important work accomplished as part of this initiative.”

Volume 2 updates the official list and map of federal Indian boarding schools to include 417 educational institutions across 37 states or territories at the time. It provides detailed profiles of each school and identifies at least 973 American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children who died while attending federally operated or assisted schools. There is. It also identified at least 74 marked and unmarked burial sites at 65 different school facilities, costing the U.S. government $23.3 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars for fiscal year 2023 between 1871 and 1969. It is estimated that the above amount was allocated to the Indian Federal Boarding School System. So are other similar institutions and related assimilation policies.

In the process of publishing these two volumes, Department staff and contractors reviewed approximately 103 million pages of federal records. Secretary Haaland and Assistant Secretary Newland also met with government officials and Indigenous leaders in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand to address the legacy of similar assimilation policies, including residential schools and educational institutions. I understood the process.

The report includes eight recommendations from Assistant Secretary Newland to the federal government aimed at supporting the nation’s path to healing:

Announcing formal recognition and apology from the U.S. Government regarding its role in the adoption and implementation of the Federal Indian Residential School Policy. Investing in remedies for the current effects of the Indian Federal Residential School System. Establish a national monument to recognize and commemorate the experiences of Indian tribes, individuals, and families affected by the Federal Indian Residential School System. Identifying and repatriating the remains and grave goods of children who did not return from Indian Commonwealth residential schools. Returning the site of a federal Indian boarding school to the tribe. Telling the story of the Federal Indian Boarding Schools to the American people and the international community. Invest in further research into the current health and economic impacts of India’s federal residential school system. Advance international relations in other countries with similar but unique histories, such as boarding schools and other assimilationist policies.

Recognizing the damage that federal Indian residential schools and related policies have done to Native languages, investing in their restoration and preservation has become an early priority of the Biden-Harris Administration. In 2021, the Departments of the Interior, Education, and Health and Human Services launched an interagency initiative to preserve, protect, and promote the rights and freedoms of Native Americans to use, practice, and develop their Native languages. Since then, Secretary Haaland and Assistant Secretary Newland have consulted with First Lady Jill Biden and other administration leaders to learn more about how tribal nations are leveraging federal investments to revitalize their native languages. traveled with them. The government plans to roll out a new 10-year mother tongue strategy by the end of 2024.

Communicating the impact of these residential schools is the guiding purpose of the Federal Indian Residential Schools Initiative, and Secretary Haaland’s op-ed draws on her own personal history. At the end of 2023, Secretary Haaland and Assistant Secretary Newland completed the Path to Healing. The tour was a historic tour of 12 locations across the country, giving Native American survivors the first opportunity to share their experiences in federal Indian residential schools with the federal government. . The “Pathway to Healing” event included an opportunity to provide trauma-informed support to survivors through the Department of Health and Human Services’ Indian Health Service and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. The reflections of many of these individuals are included in Volume 2, and the transcripts are available on the Federal Residential School Initiative website.

The department also launched an oral history project to document and share with the public the experiences of generations of Native children who attended the federal Indian Residential School System. With a grant from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and funding from the Mellon Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition is currently interviewing survivors to create what will be a collection of first-person stories. We are doing The Department and the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, part of the world’s largest museum, research, and education complex, will explore the best ways to share with the public the history of the Federal Indian Residential School System and its role in the United States. We are partnering for this purpose. Developments are proposed that focus on the previously untold experiences of survivors.

Some facilities classified as historic federal Indian boarding schools operate in the United States without assimilationist intentions or practices, including schools operated or funded by the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE). Continuing. BIE considers the spiritual, physical, religious, and cultural aspects of Native learners and provides quality educational opportunities from early childhood through life. Similarly, Kamehameha Schools throughout the Hawaiian Islands provide important educational services, including essential language preservation curricula that are unique and foundational to Native Hawaiian communities.

Both volumes of the report and associated appendices are available on the Bureau of Indian Affairs website.

###