On a recent morning, Tony Arias and Idelfonso Armenta, hosts of a popular show on Arizona radio station La Campesina, invited listeners to talk about the election. “Miraza,” Arias said, leaning into the microphone. “Donald Trump or Kamala Harris? We’d love to hear your thoughts.”

Arias and Armenta’s show is called “Los Chavorcos,” a play on the word “young geeks.” Armenta is a tall, stocky man in his 40s with a sonorous baritone voice. By comparison, Alia, who is three years younger, shorter and thinner, sounds comically cheerful. From 6 a.m. to 10 a.m., the two will provide jokes, musical hits, and news to an audience of more than 100,000 Latino workers. The show sounds like a conversation between friends, but it had a large enough audience to get President Joe Biden’s attention. Last year, during his re-election campaign, he took calls from the Oval Office and fielded questions about immigration, the economy and disinformation.

Biden made a characteristic effort to connect personally during his appearance. “I’m looking at a statue of Cesar Chavez, the guy who almost lost his life in the 1972 election,” he told organizers. La Campesina, which broadcasts from a red brick building in the Phoenix neighborhood of Eastlake Park, was founded in 1983 by Cesar Chavez. Arias and Armenta sit across from each other at a wooden desk made by one of Chavez’s brothers. On the morning of my visit, Armenta was at the console and Arias was checking the incoming reactions, bouncing the needle to the sounds of the Norteño. “We have to broadcast their audio,” Arias said, rolling her eyes as she scrolled. “We will be scolded.”

Both started working in radio early. Originally from the Mexican border town of Nogales, Armenta hosted his first show, “De Corazon a Corazon,” when he was 17 years old. He then moved to Arizona and worked in construction and radio jobs until he heard about a job opening at La Campesina. Arias started his own show in Phoenix and developed a following among the city’s immigrant community. On and off the air, he became a voice for families terrorized by the fervently anti-immigrant former Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio.

Currently, its activities have expanded to include Arizona, California, and Nevada. In Las Vegas, an army of service workers, including bellhops, cooks, servers, and stewardesses, come to work each morning. As part of an effort known as “La Corrida,” farmworkers who follow crops from state to state carry radios with them wherever they go. In the border town of Yuma, the station’s signal flows south into Mexico, where it is known as “la estación gringa.”

Of the seven battleground states, Arizona has the highest proportion of Latino voters, accounting for one-quarter of the electorate. But communication from Mr. Trump and Ms. Harris has been slow, and an August poll found that half of Latino voters had not heard from either campaign. A major advocacy group recently sent a letter to Republican and Democratic leaders condemning both parties for their “terrible support.” For Arizona’s Spanish-speaking residents, important political conversations are taking place not at election events or town halls, but in trusted news outlets like La Campesina.

In 2020, Biden won Arizona by more than 10,000 votes, but Harris fell behind there after a promising start. The Chaborcos weren’t too concerned about the swings in the polls. They wanted to hear from listeners and share the microphone. “This is our way of saying, ‘Your opinion is valuable, so go ahead and jump in,'” Armenta said. He flashed Arias a hand signal, 20 seconds. The first song of the hour was coming to an end, but Arias was still trimming people’s audio.

With time running out, Arias took to the microphone and began his segment. “Oh Dios, how hard it is to go from ‘I love you’ to ‘I love you,'” he said. “But we don’t have enough money to even go to the bamboo shoots.” The two hosts started laughing, then moved on to people’s opinions.

One listener focused on President Trump’s false claim that immigrants in Ohio were eating dogs and cats. Armenta replied, “All we can say is that it is Mitote,” which is an unsubstantiated rumor. “It’s very easy to talk without any basis, without any evidence to support what you’re saying. And that’s one of the qualities of Donald Trump.”

Before calling for a music break, the host asked a question to the listeners. Who, in their opinion, will make their lives better?

The studio phone rang. “Good morning, campesino,” Armenta said. “Who would you like to talk to?” He covered the receiver and turned to Arias, “His name is Sigifrid.”

Arias answered the phone. Please tell me what you think. ”

“I don’t think the people who are calling and sharing their opinions on Kamala Harris have any idea what they’re talking about. It’s the same old cantarator” — the same old refrain. “I don’t think anything will change if she wins,” he said. “With Donald Trump, we’re going to have a better chance,” he continued, “and a lot of things will benefit us: closed borders, lower taxes, more jobs.”

“What do you mean by closing the borders?” Armenta asked.

“Things are a little tough in this country these days. And the more people come, the worse the situation gets.”

That morning, Sigifrid was in the minority. The callers, mostly women, overwhelmingly sided with Harris. But Trump has a narrow lead in the Grand Canyon State. “I think people need to understand that the direction this country takes is in their hands,” Armenta concluded. A large portion of Latino voters remained undecided, but if Arizona had become a battleground state in 2020 after more than two decades of Republican dominance, it was partly because of them. “The best thing we can do is stay informed,” Arias continued. “And most of all, get out and vote.”

Few current members of La Campesina met Chavez, who died in 1993, but he resonates with their imaginations. The walls outside the studio are lined with memorabilia that convey his image, including paintings, photographs, vinyl records and cereal boxes.

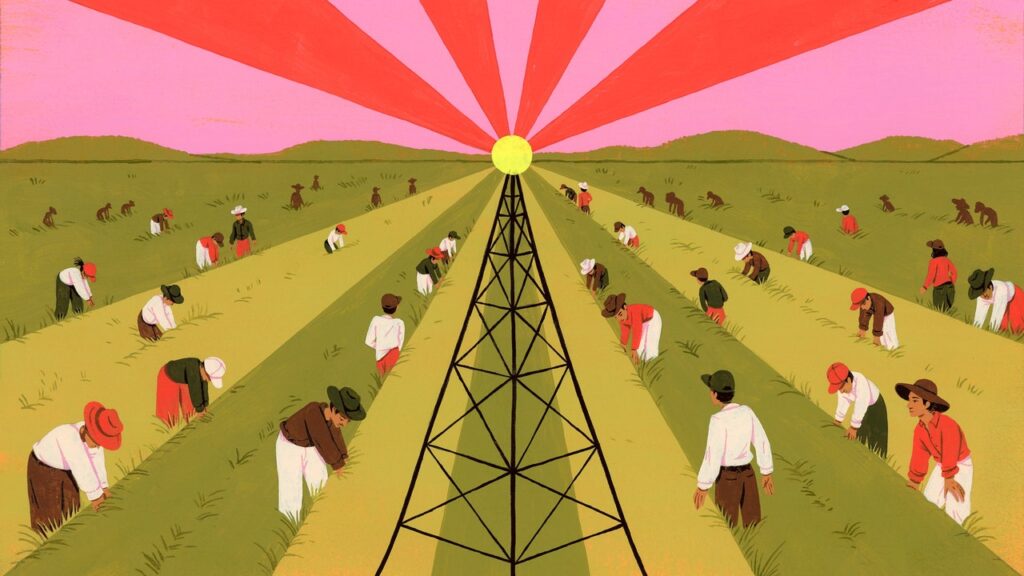

Chavez understood early on that organizing seasonal agricultural workers required effective mass communication. When he moved to California’s Central Valley in 1962, he installed a mimeograph machine on his back porch and printed flyers. “This was back when no one knew anything about Cesar Chavez,” his younger son, Paul, told me. He packed boxes of flyers into his old Mercury station wagon and asked eight children to hand out the flyers. “He left a couple of us in one corner and a couple of us in the other corner, and our job was to hand out flyers,” Paul said. “He really handed out flyers all over the Central Valley.”

As the message spread and trade unions took shape, Chávez established a printing press and began publishing a newspaper called El Marcriado (“The Rebel”). His aim was to communicate directly with workers and counter producers’ efforts against unions. “People have been trying to organize farm workers for over 100 years,” Paul said. “All attempts were brutally crushed.” Union members were regularly beaten, arrested, stripped, and chained. They were threatened with loaded guns, and at least five were killed on the picket line or while organizing workers. Chavez believed that music was a way to reach people secretly. Farm workers often carried transistor radios with them to ease the drudgery of their work. Paul remembered his father often saying, “If we had a radio station, instead of talking to hundreds or thousands of people a day, we could talk to 50,000 people a day.”