Some polling organizations have concluded that black men tend to be conservative. they are asking the wrong question. Black men have always transcended ideological boundaries. We have nuanced political views that don’t fit neatly into the liberal versus conservative binary. The real question is: What can we do to get more black men, especially young men, involved in the political process?

Nearly half (41 percent) of Black people believe in the power of coming together to make change, but 22 percent are cynical about politics and elections, and the rest are cynical about politics and elections, according to new research from a four-year project that studies Black voters. 18% of people are said to be susceptible. To this disillusionment. Millions of young black men fall into a cluster that researchers call “natural cynics.” They are not convinced that their vote will change their material situation. Researchers argue that their cynicism is justified because politicians and organizations are failing to serve their interests. POWER Interfaith and others commissioned this study because they wanted to better understand the diversity of Black voters, especially Black men.

We represent some of that diversity. Generation Xer Greg Edwards grew up in a segregated town in New Jersey in the 1970s. There, every effort to make progress was met with resistance. Marcus Bass is a millennial from North Carolina who became politically awakened during the Black Lives Matter protests of the 2010s. But in both our work as community organizers and in our personal lives, we hear the same thing. Many young black men feel ignored, misunderstood, and completely betrayed by the political system.

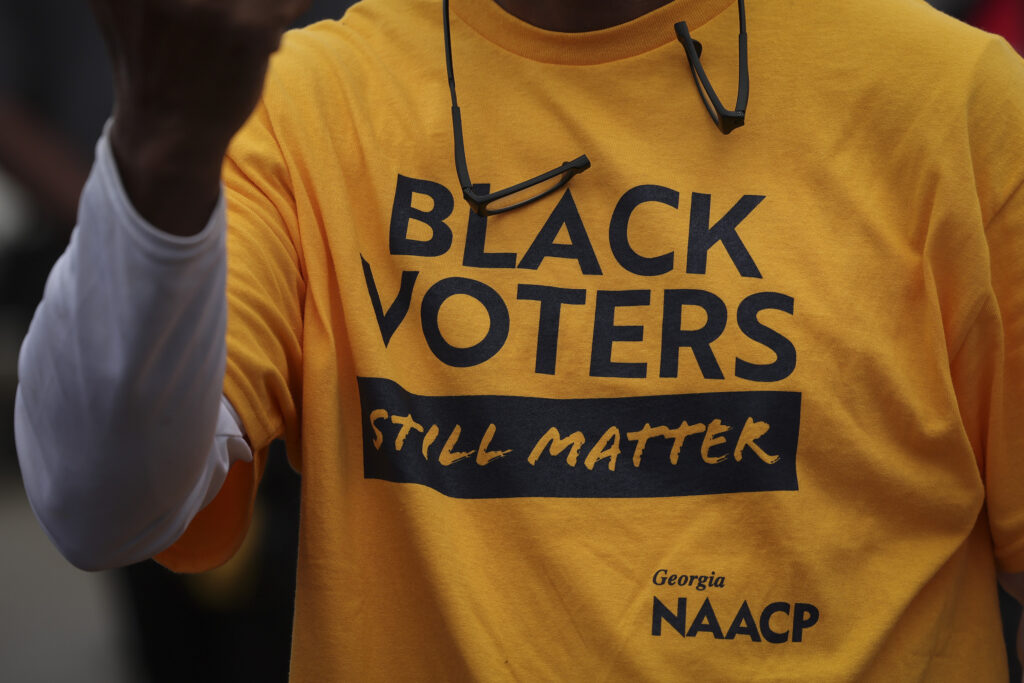

A member of the audience wears a Georgia NAACP “Black Voters Still Matter” T-shirt on Dec. 3, 2022 in Hephzibah, Georgia. A member of the audience wears a Georgia NAACP “Black Voters Still Matter” T-shirt on Dec. 3, 2022 in Hephzibah, Georgia. Win McNamee/Getty Images

If we are serious about protecting our democracy, we cannot afford to condemn and shame young black men who feel this way. Simply telling them that their ancestors faced a fire hose to win the right to vote will not move them, especially when they are protesting the same injustices today, including police brutality. What we need to do instead is break down their isolation and help them feel seen and heard. We must create spaces that truly embrace Black men and encourage open dialogue without imposing conformity or reducing their diverse experiences to a monolithic narrative.

In Pennsylvania, POWER Interfaith is creating a space for young Black men and women to have authentic conversations that listen more than preach. Older members of the “Legacy Civil Rights” generation are hosting soul food dinners in their homes or church basements, where young people can talk freely about their lives. At a recent dinner, a non-judgmental, cross-generational conversation revealed that young people who hadn’t voted since 2016 realized that while they may not be interested in politics, they are. I did. Government policies will affect the rent he pays, he may be denied a mortgage, and he may miss out on a promotion. When he saw the connection between what was on the ballot and his daily life, he decided to return to the political process.

In the South, the North Carolina Black Alliance is partnering with lifestyle influencers, political party promoters, and fitness groups to start political conversations in a natural, not forced, way. For example, a running club in Charlotte draws more than 300 black youth each week. Events like this, which bring together young Black people to foster joy and build community, are more effective at bringing people together than campaign rallies. Culture creates a bridge between what people love and what they can do to make their lives better.

What research shows, and what we’re seeing at dinner tables in Philadelphia and running clubs in North Carolina, is that when legitimate cynics meet each other, they feel less alone. They realize there is strength in their numbers. Even if you feel like your vote doesn’t matter, you can use collective power to decide what laws and policies are passed. They can hold politicians accountable for providing real solutions for their communities. This is where the magic happens, not in the war rooms of political consultants, but in the streets and everywhere young black people come together to demand better for themselves.

Love for our community knows no divorce clause. We are united by a common history and a common hope for the future. That’s the beauty of our work as community organizers. It forces us to confront our differences, sit with our discomfort, and ultimately choose one another. Across all our differences, we can build a multiracial democracy that works for everyone. No matter who wins in November, the work continues.

The Rev. Gregory Edwards is interim executive director of Pennsylvania Power Interface, and Marcus Bass is vice president of the North Carolina Negro Alliance.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own.