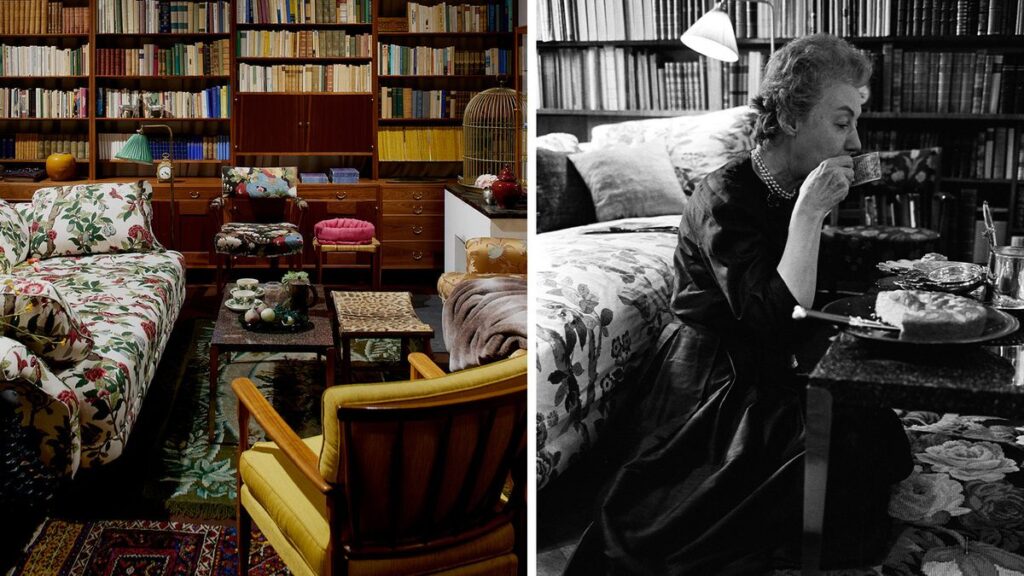

Estrid Eriksson, the energetic founder of pewter factory-turned-interiors brand Svenskt Ten, lives a few floors above her shop on Strandvägen, Stockholm’s famous and majestic tree-lined waterfront promenade. I was there. Her apartment was decorated with furniture designed and sold by her brand, souvenirs from overseas trips, and items found at flea markets. It has changed over the years and represents her belief that, as she wrote in a 1939 essay, “our house is never finished.” But 19TK’s photos show a particularly elegant yet relaxed moment. Erickson, wearing a tuft of pearls and a brocade dress, lies under a fur blanket on a floral-print sofa while reading a book. Her dog sprawls at her feet, and her cat sits just a few feet away at a zebra-print table. It’s a cozy, welcoming, and fun space, qualities that define her Swedish modernism.

This stunningly faithful recreation of a living room is part of the exhibition “Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home” at Stockholm’s Liljevarhiss Museum, which celebrates its 100th anniversary this year. Organized by Svenskt Tenn’s chief curator Karin Södergren and independent curator Jane Withers, the show features a wide range of furniture, objects and never-before-exhibited ephemera from the company’s extensive archives. Spread out in 13 themed rooms. While many of the exhibits will be familiar to fans of Svenskt Ten, particularly the exuberant Joseph Frank botanical textiles and sparkling pewter tableware, the focus of this retrospective is on Eriksson’s values. The point is how permanent a view is.

“Family Philosophy” explores 100 years of Svensk Ten

Estrid Eriksson and Josef Frank_Sweden Ten archives and collections in the shop

(Image credit: Lennart Nilsson)

Although Erickson and Frank have had their own exhibitions in the past, A Philosophy of Home marks the first time that their stories are brought together in the context of the brand they built. “It’s very exciting,” says Maria Veerasamy, CEO of Svenskt Tenn, about organizing the exhibition. “Seeing everything come to life, witnessing a century of creativity and craftsmanship, creates a moment of reflection and pride.”

It’s unusual for a century-old furniture brand to exist today, let alone remain relevant and beloved in the design world. However, Svenskt Tenn managed to be saved thanks to Ericsson’s vision for the company. She championed craftsmanship, had an instinct for finding talented designers, and challenged societal norms about what a home should represent. But overall, she supported a liberal definition of modernism that allowed for personal expression. With this exhibition, she finally received the recognition she deserved.

Estrid Eriksson 1939. Photo from Svenskuten Archive

(Image credit: Sigfrid Ericson)

“She’s obviously known in the Swedish and Scandinavian context, but she deserves to be a bigger figure in the world as a whole,” Withers says. “The story of this dynamic young woman who came from a relatively small town, came to Stockholm, was active in very progressive circles, and created this extraordinary vision of how we should live. is very attractive.”

Born in 1894, Eriksson grew up in Hjor, a small town about 200 miles southwest of Stockholm, where her family ran a popular hotel. Through this experience, she learned about hospitality and creating a homely atmosphere, which became a core part of Svenskt Ten. She left home at the age of 19 to study at what is now Konstfack University of Arts, Crafts and Design, and was drawn to it. Written by feminist social theorist Ellen Key. The work of modernist industrial designer Gregor Paulson. The interior design was created by Karin and Carl Larsson, a couple who believed that the home could be a platform for social change. After graduating, she worked for several interior design firms in Stockholm before opening Svenskt Tenn with her friend and business partner, sculptor and silversmith Nils Vogstedt.

“Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home” on display at Liljevalks Museum in Stockholm

(Image credit: courtesy of Senskt Tenn Archive)

During the first years of business, Ericsson focused on manufacturing pewter objects (Svenskt Tenn translates to “Swedish pewter”). She collaborated with artists such as Uno Ohlen and Björn Tregarde, and often incorporated references from artifacts she saw at the Anthropological Museum in Stockholm. In addition to stocking pewter products he designed himself, Erickson sold household items and objects he found on his travels and at flea markets. “This curiosity and love of diverse cultures deeply influenced Svensk Ten’s eclectic style,” says Södergren. “She built a store not only for retail, but also for cultural exchange.” Svenskt Tenn quickly became popular, especially among progressive-minded women.

Eriksson was a smart entrepreneur and found a way to keep Svensk Ten in the press. She did photo shoots in her apartment and invited customers upstairs to see the different ways her furniture and homewares could be styled. The host has created elaborate table settings in her showroom and taught shoppers how to copy them at home. (She advises placing candles high to highlight the light and placing flower arrangements low so they don’t interfere with conversation.)

“Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home” on display at Liljevalks Museum in Stockholm

(Image credit: courtesy of Senskt Tenn Archive)

But overall, she lived the lifestyle she marketed: an early version of today’s design influencer. “She was able to take her image and use it as the basis for Svensk Ten,” says Withers. “From very early on, she was using her home as a set of stores to communicate ideas. It’s a familiar vision. She could be proto-Conran.”

In the 1930s, Erikson began a decades-long collaboration with Frank, who had fled Austria to Sweden to escape the rise of anti-Semitism and fascism. Frank ran the design company and shop Haus & Garten in Vienna, where he encouraged his clients to mix and match patterns, choose comfortable furniture, and embrace eclecticism. He brought this approach to Svenskt Ten and influenced Erikson’s perspective. The two worked together until his death in 1967.

Estrid Eriksson and Josef Frank photo Lennart Nilsson 1964

(Image credit: courtesy of Senskt Tenn Archive)

“When Erikson founded Svenskt Ten in 1924, she aligned herself with the general movements of modernism and functionalism,” Veerasamy explains. However, she gradually begins to challenge these ideals, and the change gains momentum with Frank’s arrival. Together they developed an interior philosophy that challenged the established Swedish style and promoted a humanistic view of the home as a place for authentic living and freedom. This was an approach in stark contrast to the more restrictive design ideals of the time. ”

Social context undoubtedly influenced this change, and the lifestyle that Svensk Ten embodied served as an example of the broader values that Eriksson and Frank wanted the world at large to see. Ta.

“The 1930s were politically difficult and frightening times, just like our own. They invented the house not only as a place of personal freedom, but as a place to live freely, and above all as a haven. “We did,” Withers said. “It’s about physical and psychological comfort. Home is a kind of backdrop, a framework. It’s not about a perfect image or anything, it’s about people being able to feel safe and enjoy being together. It’s a place where you can do that.”

“Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home” on display at Liljevalks Museum in Stockholm

(Image credit: courtesy of Senskt Tenn Archive)

To that end, Svenskt Tenn expressed a kind of stylistic omnivorousness. Items on sale include elaborately woven wicker chairs, pewter accessories molded with playful animal motifs, fabrics printed with rich botanical patterns, and minimalist silhouette tables made from expressive wood. All of which are on display at Liljevalx. The most important aspect of this sensibility was to mix the things inside the house that would evolve with the people who lived there.

In 1958, Frank wrote an essay titled “Contingencyism,” which explained the design philosophy he and Ericsson passed on through Svensk Ten, stating that “a living room in which one can live and think freely is neither beautiful nor harmonious.” “It’s not a target or photogenic,” he wrote. “It’s just a coincidence.”

As architectural historian and Frankish scholar Christopher Long explains, this essay reminds us of the value of diversity in design and experimenting outside the rules. This feels especially relevant today, when stylistic identity is rapidly metastasizing across the world (and our algorithms). Fire trend cycles promote indiscriminate consumerism.

“Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home” on display at Liljevalks Museum in Stockholm

(Image credit: courtesy of Senskt Tenn Archive)

“It’s so refreshing to come across such an open-minded idea of how humans should live, open to chaos and playfulness and certain joys in life,” Withers says. “And I think that’s why it means so much to me today.”

Erickson wanted his company to outlive him. Before retiring, Eriksson sold Svenskt Ten to a non-profit foundation aimed at promoting social welfare. Currently, this includes funding research on environmental issues and, of course, promoting Swedish craftsmanship, design and architecture. It’s a framework that allows the brand to stay true to her heritage while responding to the moment. That means the company continues to work with long-established, family-owned manufacturers and producers, while welcoming contemporary designers such as Michael Anastasiades, Karina Seth Anderson, and India Mahdavi to develop new products. “Ericsson’s approach taught me that to be authentic, you don’t have to stop. Rather, you can move forward in your own way and at your own pace,” Veerasamy says. Masu.

Interestingly, this is a vision that applies to everyone, not just Svenskten shoppers (you’d be hard-pressed to find someone in Sweden who hasn’t received something from them). Södergren hopes the exhibition will show visitors to Liljewalchs how they can apply Erikson and Frank’s philosophy to their own homes. “It’s not just a list of ‘rules’, but rather a philosophy that inspires the way we live,” she says.

“Svenskt Tenn: A Philosophy of Home” is on display at the Liljevalks Museum in Stockholm until January 12, 2025. liljevalchs.se