As has been described in science textbooks for decades, Earth’s mantle does not always move in lockstep with the overlying crust and can behave differently.

That’s the conclusion of an international team of geologists who made a mysterious discovery on Easter Island, a special territory of Chile in the Pacific Ocean famous for its giant statues.

The idea that the Earth’s crust and mantle might move together like a “conveyor belt” as a result of convection in the latter was first proposed by British geologist Sir Arthur Holmes in 1919.

His proposal provided a mechanism for large continents to drift across the Earth’s surface. This theory is based on evidence such as how continents like Africa and South America, despite being separated by oceans, appear to be compatible with each other and have matching rocks and fossils. was controversial at the time.

But now, researchers have discovered a crystalline “time capsule” on Easter Island that appears to have remained in the same place in the mantle for about 162.5 million years. This contradicts the conveyor belt theory and suggests that the behavior of the mantle may be much more complex than previously thought.

Easter Island has revealed new evidence that may question our understanding of how Earth’s mantle works. Easter Island has revealed new evidence that may question our understanding of how Earth’s mantle works. Carlos Aranguiz / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Geologically speaking, Easter Island, located about 3,200 miles off the coast of Chile, is like the arrival of spring. The oldest part of the island was formed 2.5 million years ago by a volcanic eruption on top of a not-so-old oceanic plate.

In their research, geologist Yamilka Rojas Agramonte of the University of Kiel in Germany and her colleagues set out to accurately calculate the island’s age. To do this, they focused on tiny crystals containing uranium called zircons, which are like small natural time capsules preserved in lava.

The longer the magma cools and crystals form, the more uranium decays into lead. Geologists can determine how old a crystal is by measuring the ratio of the two.

The research team discovered and analyzed hundreds of zircons in Easter Island’s oldest volcanic material. But something was different. As expected, some were formed around 2.5 million years ago, but others are much older, perhaps 165 million years ago, before the island was formed.

This posed a kind of puzzle for researchers. Further chemical analysis of the zircon crystals revealed that they all had approximately the same composition. This means they must have come from magma of the same composition as the “young” volcano.

But at the same time, there is no way these volcanoes have been active for 165 million years. Even the oceanic plates from which the volcanoes erupted are not that old.

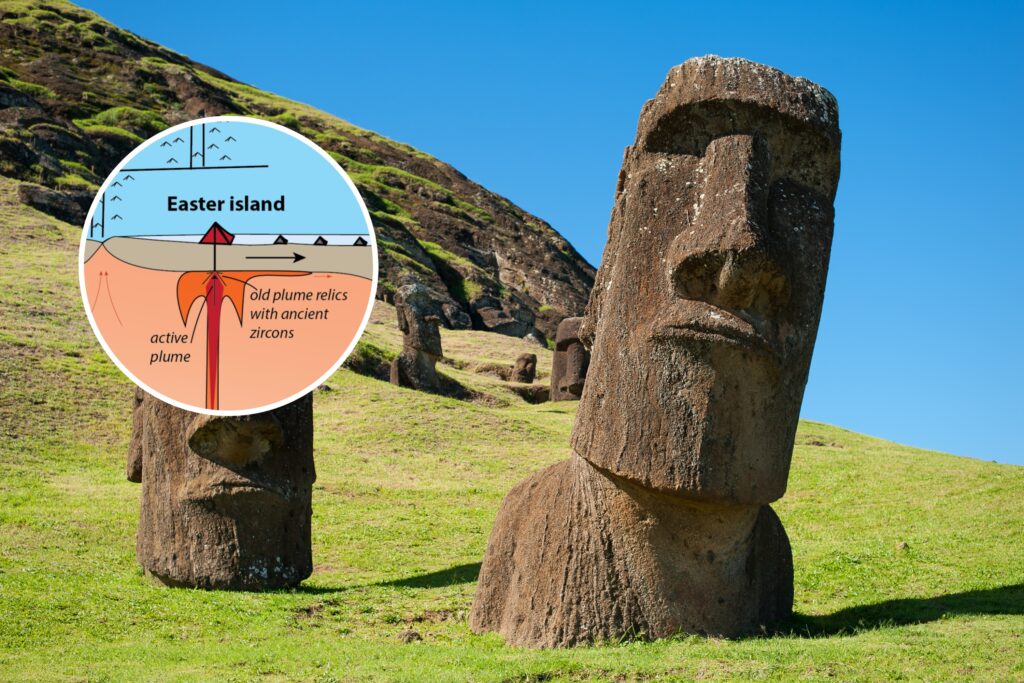

A cross section shows the interior of the Earth. It has long been thought that the mantle and the Earth’s crust move together like a conveyor belt, but new evidence suggests that the mantle’s behavior may be much more complex. A cross section shows the interior of the Earth. It has long been thought that the mantle and the Earth’s crust move together like a conveyor belt, but new evidence suggests that the mantle’s behavior may be much more complex. Blue Ring Media / iStock / Getty Images Plus

The only solution to the researchers’ conundrum is that ancient zircons must have arisen deep within volcanic activity, deep beneath the Earth’s crust and within the mantle.

Easter Island’s volcanoes, like those in Hawaii and Iceland, are driven by underlying “hot spots” — plumes of melted material rising through the mantle, like the paraffin wax that lifts a lava lamp. are.

Because the plume begins at the bottom of the mantle (at the border with the Earth’s core, which is 1,000 degrees Celsius warmer than the upper layer), the plume is essentially fixed in place.

In contrast, the Earth’s crust (and, according to traditional conveyor belt theory, the underlying mantle) moves above the hot spot. As a result, hot spots form volcanoes at different locations on the Earth’s surface over time. Like the Hawaiian Islands, different islands formed on top of a hot spot.

Perhaps the researchers reasoned that the oldest zircon found on Easter Island was evidence that the hotspot itself had been active for 165 million years.

The diagram shows the crustal structure of Easter Island. Researchers believe the volcano that formed the island contained ancient material from a mantle plume. The diagram shows the crustal structure of Easter Island. Researchers believe the volcano that formed the island contained ancient material from a mantle plume. Dauwe van Hinsbergen et al. / Utrecht University

But the problem with exploring this idea is that much of the first evidence of it, in the form of tectonic plates from 165 million years ago, is now long gone.

As study co-author Professor Dauwe van Hinsbergen, a geologist at Utrecht University, explains, the Pacific Ocean’s oceanic plate gradually recycles as its edge sinks beneath the more buoyant continental crust. (This process triggers volcanic activity beneath the overlying plate, forming a series of volcanoes around the Pacific Ocean known as the “Ring of Fire.”)

“The challenge is that the 165-million-year-old plates disappeared in those subduction zones a long time ago,” said van Hinsbergen, who has been working to reconstruct these lost plates. said in a statement.

When van Hinsbergen added the 165-million-year-old Easter Island large volcanic plateau to his simulations, he found that the landform must have sunk beneath the Antarctic Peninsula about 110 million years ago. , suggested a solution to another small puzzle.

“It happened to coincide with a poorly understood phase of mountain building and tectonic deformation at that very location,” he explained. “That mountain range, whose traces are clearly visible, may be the result of subduction of a volcanic plateau that formed 165 million years ago.”

As often happens, solving one problem only creates another. Reconstructions of past plates support the idea that the Easter Island plume may have been active for as long as 165 million years.

The “recent” volcanic eruption that started the island’s formation 2.5 million years ago not only lifted fresh material, but also remnants of older magma from the plume. This explains how the lava contains a time capsule that is 162.5 million years older than the island itself.

But the conveyor belt theory that crust and mantle move together is already challenging enough to reconcile with the observation that mantle plumes stay in one place, and these 165 million-year-old zircons The durability of makes things even worse.

“People explained that the plume is rising so fast that it is unaffected by the mantle moving with the plate, and new plume material is constantly being fed under the plate to form new volcanoes.” Van Hinsbergen said.

However, the problem with this rationale is that the old pieces of the plume should have been carried away with the rest of the mantle conveyor belt, rather than being left behind for later transport to Easter Island.

“From that we draw the conclusion that those ancient minerals could have been preserved only if the mantle surrounding the plume was as essentially stationary as the plume itself.” said Van Hinsbergen.

Researchers say this is a possibility that has previously been suggested in studies conducted in the Galapagos Islands and New Guinea.

If the researchers are right, the mantle deep beneath our feet should be moving much differently and more slowly than was long assumed.

Have a tip for a science story Newsweek should cover? Have a question about geology? Let us know at science@newsweek.com.

reference

Rojas-Agramonte, Y., Pardo, N., Hinsbergen, DJJ Van, Winter, C., Marroquín-Gomez, MP, Liu, S., Gerdes, A., Albert, R., Wu, S., Garcia. -Casco, A. (2023). Easter Island (Rapanui) zircon xenocrystals reveal hotspot activity since the Middle Jurassic. ESS Open Archive. https://doi.org/10.22541/au.170129661.17646127/v1