Changes in scores for children and parents

Across all measures, parents’ and children’s scores changed from the 2019 baseline to 2020 follow-up. Statistically significant changes are shown in the figures, and corresponding effect sizes are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

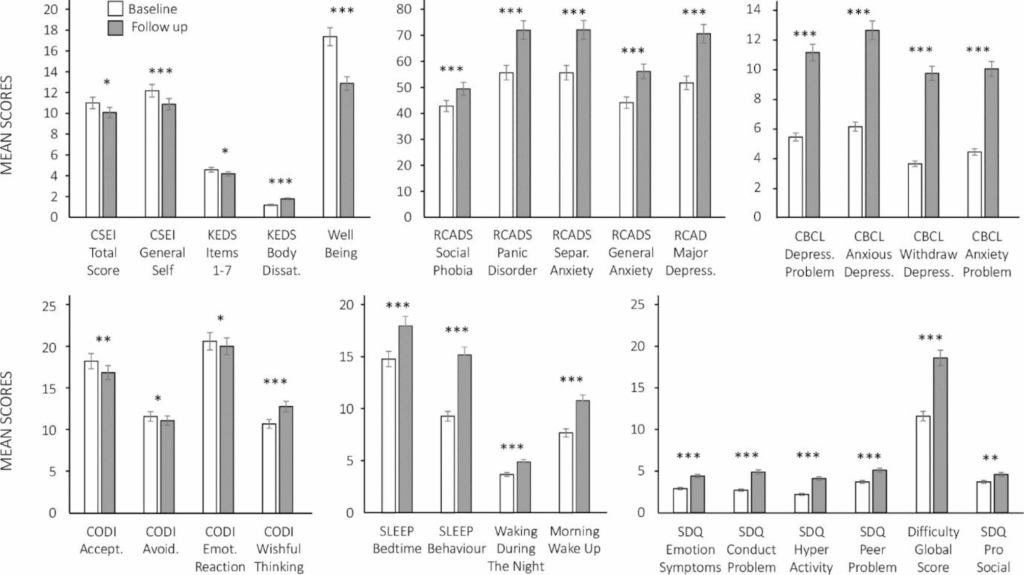

Table 3 The Cohen’s d for the repeated measures t-testsTable 4 The Cohen’s d for the wilcoxon signed Ranks testsFig. 1

Child measures at Baseline (in white) and Follow-up (in grey). Bars represent means and standard errors. The graph at the top left shows CSEI total, CSEI general, KEDS 1–7 items, KEDS body satisfaction, and child well-being. The top middle graph shows RCADS subscales. The top right graph shows CBCL subscales. The graph at the bottom left shows CODI subscales. The bottom middle graph shows sleep habits subscales. The bottom righ graph shows SDQ subscales. All the results are significant with *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Fig. 2

Parental measures at baseline (in white) and follow-up (in grey). Bars represent means and standard errors. The graph at the top left shows Shame total, and CHIP subscale. The top middle graph shows Well-being, and HFS-P subscale. The top right graph shows DASS-21 subscales. The graph at the bottom left shows Parenting subscales. The bottom righ graph shows CFQ subscales. All the results are significant with *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Fig. 3

Lifestyle measures and HbA1c at baseline (in white) and follow-up (in grey). Bars represent mean or median scores and standard errors. The graph at the top left shows children’s physical activity subscales. The second graph shows HbA1c, and the third shows LBCL subscales. The top righ graph shows RCADS obsessive compulsive scores. The two graphs at bottom show the children’s dietary subscales. All the results are significant with *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Figure 1 shows the mean scores for the child-completed self-report measures and parent-completed child measures at baseline and follow-up. Starting at the top left corner, it can be seen that children’s self-esteem (total and general), measured by CSEI, decreased. The same was also seen for children’s well-being scores, which shows that children had poorer self-esteem and well-being at follow-up compared to baseline. KEDS body dissatisfaction scores increased from baseline to follow-up, although children’s eating disorder scores (KEDS items 1 to 7) decreased. All child mental health scores (T-scored RCADS, raw CBCL, and SDQ subscales) showed increases with large effect sizes. These follow-up scores fell within a clinical range according to each measure’s cut-off point. Their CODI scores, pictured at the bottom left, indicate that children showed a decrease in acceptance, avoidance, and emotion reaction coping at follow-up; in addition, they also showed an increase in wishful thinking coping scores. The bottom middle graph shows the sleep habits subscales: there was an increase in sleep bedtime, sleep behaviour, waking during the night, and morning wake up scores, which all indicate that children experienced more sleep-related problems during the pandemic.

Figure 2 shows mean scores for the parental-completed self-report measures. The top left graph shows that shame total score decreased from baseline to follow-up. In a similar manner, CHIP scores for subscales 1, 2, and 3 also showed a decrease. There was a decrease in well-being scores from baseline to follow-up, with large effect sizes. The HSF-P scale scores showed a decrease, whilst the HFS-P worry scale scores showed an increase from baseline to follow-up. The top right graph shows the DASS-21 subscale scores for depression, anxiety, and stress. All three subscale scores increased from baseline to follow-up, with large effect sizes. These increases are also deemed problematic according to the cut-off scores provided by the scales’ authors (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). At the bottom left, the parenting subscale shows a decrease in score from baseline to follow-up. The bottom right graph shows the six CFQ subscales; scores on five out of six subscales show a decrease from baseline to follow-up, whilst the CFQ parental weight shows an increase.

Figure 3 shows mean scores for the children’s lifestyle measures and HbA1c values. The top left graph shows the children’s physical activity subscale scores. Sedentary behaviours are shown for weekdays and weekends; much of this time was spend playing video games and watching online content. Both scores show an increase from baseline to follow-up. Children’s activity levels were already low at baseline, and it is noteworthy that all parents reported that their children could not engage in any physical activity during the lockdown. The top middle graph shows that HbA1c values increased from baseline to follow-up, with about half of the sample scoring below 7.5 HbA1c in baseline, while only 12 children had such scores in the follow-up. This shows that many children’s diabetes status changed for the worse, from managed to unmanaged. The next graph shows the LBCL food score, and that physical activity and situation scores decreased from baseline to follow-up. RCADS score shows an increase in obsessive compulsive behaviour. The bottom graphs show children’s dietary behaviour – their intake of recommended foods and fluids (vegetables, fruit, and water) or discouraged foods and fluids (foods hight in salt, sugar, and fat, and carbonated sweet drinks). There was a decrease in fruit and vegetable consumption in terms of daily and weekly basis, while the consumption of water declined from baseline to follow-up. Conversely, discouraged food (non-core) consumption, already high at baseline, further increased during the lockdown.

Physiological measures

Inspection of the data from baseline to follow-up for the physiological measures with Pearson’s product moment test-retest (TR) correlations indicated moderate to strong relationships: (i) HbA1C = 0.85, p <. 001; (ii) BMI percentiles = 0.79, p <. 001; (iii) Height = 0.99, p <. 001; and Weight = 0.98, p <. 001 (strong = 0.80 or above and moderate = 0.50 to 0.79; (48; 49). There was a small increase in child height from baseline to follow-up (t = -4.79, p < .001, d = 0.06) but no changes in their weight. Consequently, there was also a small decrease in their BMI percentiles (t = 2.20, p = .031, d = 0.17). It is worth noting that the anthropometric measures at follow-up may not have been fully up to date, because outpatient visits were curtailed by the pandemic.

Reliable change indices for well-being and mental health

The findings for the repeated measures t-tests showed that the mental health and well-being of parents and children worsened during the pandemic lockdown. No notable changes were found for the lifestyle related variables so they were not explored in the regression analysis.

Children’s well-being at follow-up

A hierarchical regression was run to predict children’s well-being scores at follow-up after inspecting the pattern of correlates for the RCIs and those for the follow-up scores (see Table 5). At step one, children’s baseline well-being scores were controlled for and accounted for 10% of the unique variance in children’s follow-up well-being scores (F (1, 68) = 7.54, p = .008). The addition of the five predictor variables in step two accounted for an additional 27% of the unique variance (F (5, 63) = 5.41, p < .001) and the full model accounted for 37% of the unique variance in children’s well-being follow-up scores (F (6, 63) = 6.17, p < .001, post hoc power = 0.99 and Cohen’s f-squared = 0.59). Examination of the VIF (1.00 to 1.96) and tolerance (0.51 to 1.00) values indicated that there were no violations of regression diagnostic assumptions.

Table 5 Regression coefficients for Predicting Children’s Well-being at Follow-Up; parental outcomes; and Parental Mental Health RCI scores

Parental outcomes at follow-up

Preliminary correlational analysis identified that the best predictors of parental outcomes were the RCIs derived from their self-report measures (e.g., DASS-21 RCI depression scores) rather than the baseline or follow-up scores, so the former were used to build three regression models of parental outcomes (see Table 5).

The model for predicting: (1) parental Shame RCI scores accounted for 26.5% of the unique variance (F (3, 66) = 7.93, p < .001, post hoc power = 0.99, Cohen’s f-squared = 0.36); (2) parenting style sum RCI scores accounted for 18.5% of the unique variance (F (3, 66) = 4.99, p < .01, post hoc power = 0.92, Cohen’s f-squared = 0.23); and (3) child feeding sum RCI scores accounted for 27.6% of the unique variance (F (3, 66) = 8.39, p < .001, post hoc power = 0.99, Cohen’s f-squared = 0.38). No violations of regression diagnostic assumptions occurred during the modelling of parental outcomes: VIF = 1.04 to 1.15 and Tolerance = 0.87 to 0.96 (Model 1); VIF = 1.07 to 1.26 and Tolerance = 0.79 to 0.93 (Model 2), and VIF = 1.01 to 1.13 and Tolerance 0.89 to 0.98 (Model 3).

Parental mental health at follow up

Inspection of the parental mental health RCIs identified that three models could be derived from the data (see Table 5). In Model 1, child feeding sum RCI scores accounted for 5.8% of the unique variance in DASS-21 depression RCI scores, (F (1, 68) = 4.17, p < .05, post hoc power = 0.56, Cohen’s f-squared = 0.06.). In Model 2, HFS behaviour RCI scores accounted for 6.0% of the unique variance in DASS-21 anxiety RCI scores, (F (1, 68) = 4.36, p < .05, post hoc power = 0.56, Cohen’s f-squared = 0.06). In Model 3, shame RCI and HFS behaviour RCI scores accounted for 16.9% of the unique variance in DASS-21 stress RCI scores, (F (2, 67) = 6.82, p < .01, post hoc power = 0.92, Cohen’s f-squared = 0.20, VIF = 1.05, Tolerance = 0.95). Model 1 and Model 2 were found to have low post hoc power and Cohen’s f-squared values because of the small amount of unique variance accounted for in each model in relation to the sample size (N = 70). These findings would need to be replicated to reliably identify the strength and direction of the relations between the predictor and outcome variables.

Parents’ responses to a questionnaire about the impact of COVID-19 lockdown

Table 2 summarises the distribution of sample responses from parents who answered the questionnaire about the impact of COVID-19 in 2020. It can be seen that lockdown has had a negative impact on parents’ lives in all aspects, except family finances (reflected in question number 2).

To provide more detail to the responses, each question was followed up with a prompt asking parents if they had anything to add.

Q1. A total of 32 parents commented. Of these, 28 stated that they missed seeing their friends and attending family gatherings; two of the parent responders were divorced and one reported that his child missed her mother. One mother reported that her husband was not in Kuwait and that she was missing a family gathering as a result; another mother divulged that her only child hates her father because of his work as a policeman which keeps him away from the home.

Q2. Of seven respondents, five answered that they had no present income and two reported that they had lost their employment.

Q3. Of the 22 parents who provided comments, five answered that they had been careless; three reported experiencing feelings of fear, whilst two others described shouting and feeling nervous regularly. Stronger anger issues were acknowledged by three of the parents; three others reported high levels of caring, concern, and associated strictness, three mothers said that they had more responsibilities in the absence of their husbands. One father said that COVID-19 had impacted negatively on the relationship between him and his child, as “he was not there when he was supposed to be.” Another mother said her behaviour had bounced between being strict and careless. “Money shortages made me feel that I could not keep up with my family expenses,” she explained.

Q4. A total of 29 parents commented on this question. Ten revealed they had experienced depression, weight gain, and anger issues; six reported suffering from sleep problems, stress, and nervousness. Ten had experienced anger issues, anxiousness, stress, and fear. Three of the parents said they were constantly fearful, and that life was not enjoyable anymore.

Q5. Twenty-eight parents commented on this question; 24 reported their children had suffered from high blood sugar; two children with high blood sugar had been admitted to hospital, and two reported levels of low blood sugar in their children.

Q6. Out of nine respondents, four reported being fearful of their children having high blood sugar; three revealed that their children had refused their medicine, one child was said to care more about medicine than previously, and one child insisted that they did not care about their medicine.

Q7. Of 34 parents who commented on the question, 10 reported that their children had experienced stress, nervousness, and a reluctance to go out in public. Five reported fearfulness and hyperactivity in their children related to COVID-19 and noted that most had many questions about it. Two reported that their children had lost interest in food and play and became careless as a consequence of emotional anxiety about the pandemic. Two reported child bedwetting and anger as symptoms of their children’s reactions to COVID-19, while another two said their children were worried about the future. Additionally, three reported their children had experienced sleep problems, nightmares, and/or that they wanted to sleep near their mothers. Two reported that their children have tended to cry a lot since the outbreak of the pandemic, have a fear of death, and are more anxious or overly sensitive. Four revealed that their children wanted to self-isolate and did not want to play outside. Three reported that their children had experienced sadness and loneliness due to the pandemic, and had missed their friends.

Q8. Twelve respondents commented on the question. Five reported a lack of access to hospital appointments; four reported delays in receiving medicine, two reported sleep issues and concerns about clinic closures. Lastly, one parent reported that they or their child had experienced eye problems and been refused routine care.

Q9. Of 29 parents who commented, most reported that their children had experienced sleep issues (including insomnia), eating issues, and a decrease in physical activities. Additionally, two reported that their children had been repeatedly asking for non-healthy food. Three parents reported that their children had experienced insomnia.

Q10. A total of 32 parents commented on this question. Most reported sleep issues, lack of exercise, and eating-related issues (eating significantly less or more food or refusing it). Three parents reported their children asked for non-healthy food.

Q11. Fifteen parents commented, of which 12 reported experiencing feelings of fear about life and the future, one reported fear of death, and two revealed they did not trust the future and worried about it.

Q12. Twelve parents offered comments, of which four said that life had changed for the worse, three described the challenging effects of no school, no work, and a lack of social gatherings. Two parents said they no longer experienced enjoyment in their lives and another two reported major changes in their thoughts and beliefs about life. Only one parent reported losing their employment, and as a result, a major impact on their daily routine.